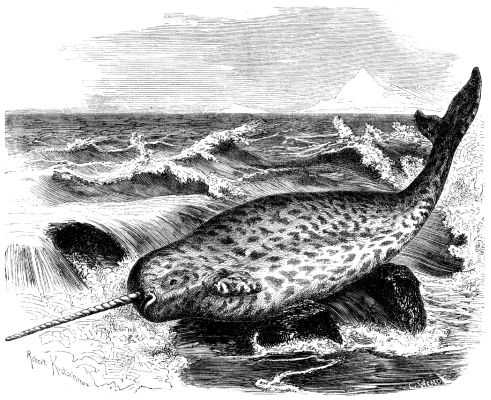

Narwhals are having a bit of a moment. Barnes and Noble lists six recent narwhal-themed titles (https://www.barnesandnoble.com/blog/kids/6-books-narwhals/) and GoodReads has a whopping twenty-five (https://www.goodreads.com/list/show/105601.Narwhal_Children_s_Books

).

But why?

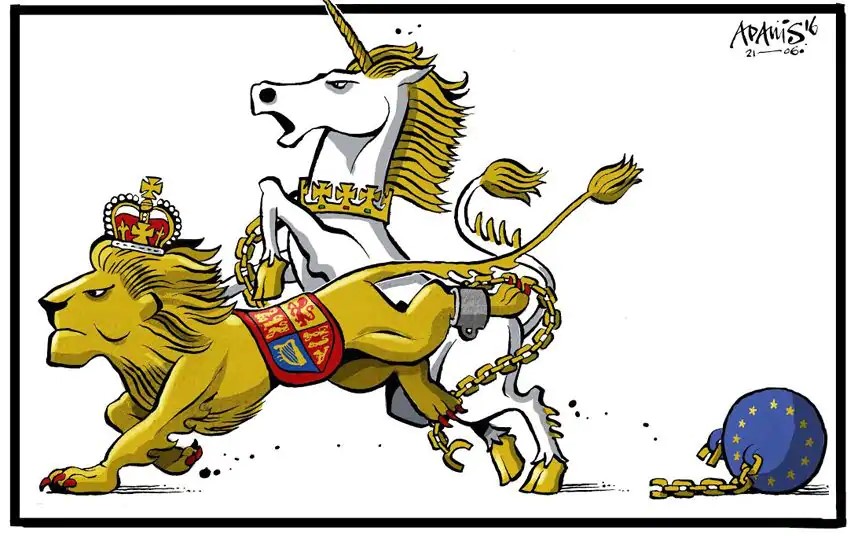

I mentioned this to my sister and she said, “Yeah, because they’re like unicorns for boys.”

Okay, I thought, narwhals are attractive because they’re real and the “real” and “scientific” is associated with masculinity, versus “feminine” fantasy and romance. (Of course, historically unicorn iconography is much more ambivalent about gender but we’re talking about reductive marketing aimed at dividing kids into pink and blue sections of the toy/clothes sections at Target, etc.) I looked at my narwhal cellphone cover and thought it looked kind of gender neutral. Maybe narwhals were breaking down barriers between unicorns “for girls” (or at least not for “boys”) and making unicorns for everyone!

I thought I had cracked the narwhal question.

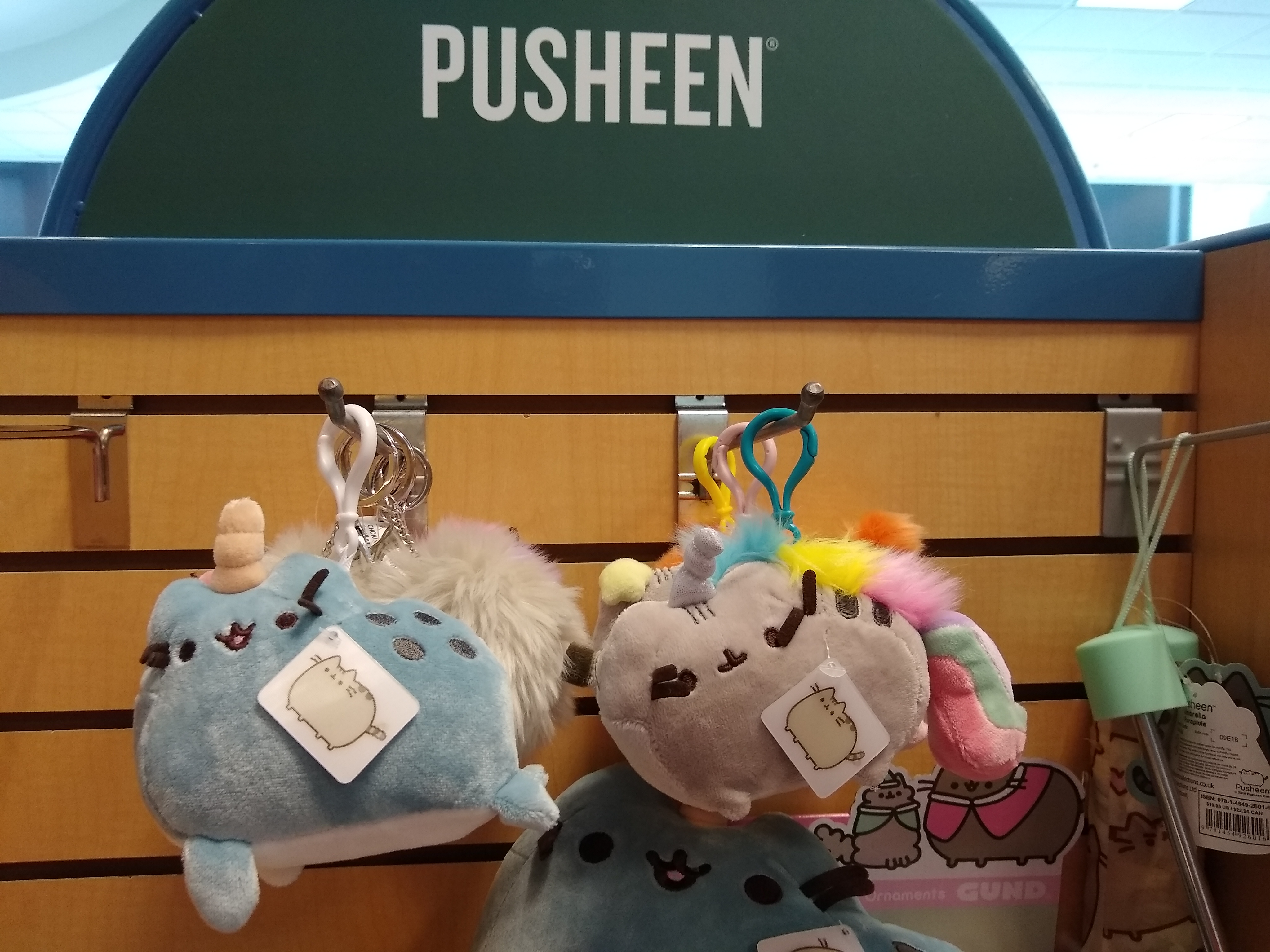

But then… I saw a giant, hot-pink plushie narwhal at the local CVS. And then I went to Barnes and Noble and saw this:

Why does a cat need to be either a unicorn or a whale? This confuses me. Self-respecting cats know that they are completely adequate as cats and need not compromise their cat-ness with sorbet-coloured manes and vestigial flippers.

And then I saw this:

Note the pearlescent and purply narwhal items stacked next to ye olde rainbow unicorn on the middle and bottom shelves.

Purple sparkly narwhals are not about “the real” or about the scientific existence of unicorns.

But at the same time, narwhals are not not about “the real.” The Narwhal and Jelly series is delightfully absurdist and Not Quite Narwhal plays on the way invisibility and non-existence aren’t at all the same and definitely messes with binary categories. Making a purple narwhal tape dispenser is playing on the image of an existent animal in a slightly different way than on a mythological figure if only by deliberately messing with “natural” representations.

But what does all this fun re-colouring and cutesifying of narwhal products do for a species threatened by the degradation of polar ice?

You kind of hope that the reality of narwhals in nature will inspire owners of narwhal plushies to get invested in maintaining the habitats of these amazing animals and investing emotionally (and eventually politically) in environmental protection. I know that’s not the aim of product designers spinning off and innovating on the unicorn craze, but I hope it happens, nonetheless.

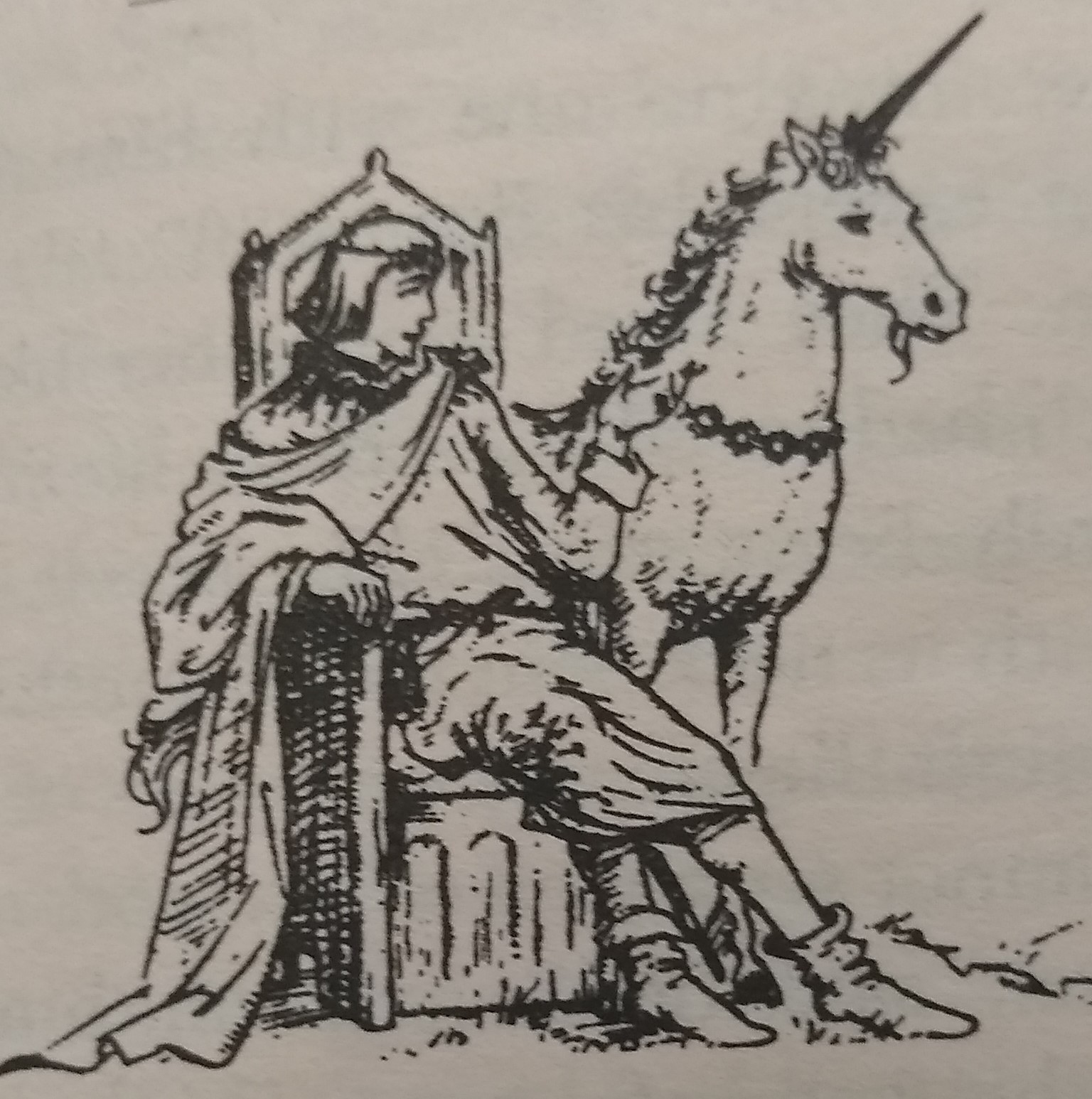

Anyways, if you are looking for some fun reading on narwhals that isn’t reducing them to commercial bunkus, National Geographic’s Mystery of the Sea Unicorn features a great 1694 illustration of a narwhal and an imaginatively rendered equine sea-unicorn. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/phenomena/2014/03/18/the-mystery-of-the-sea-unicorn/

There’s also a good summary on the World Wildlife Fund site: https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/unicorn-of-the-sea-narwhal-facts

queen)

queen)

obably the first “hard” book I read. The next time I read such a hard book was when I was sixteen or seventeen and read All Quiet on The Western Front (everyone dies in the cultural apocalypse of the First World War). (To my shame, I came late to The Diary of Anne Frank.)

obably the first “hard” book I read. The next time I read such a hard book was when I was sixteen or seventeen and read All Quiet on The Western Front (everyone dies in the cultural apocalypse of the First World War). (To my shame, I came late to The Diary of Anne Frank.)